April 2025

An algorithmic challenge – appropriate or inappropriate shock?

Daniel Hinchliffe, Clinical Scientist (Invasive Cardiology), Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust

Disclosure: The author has no conflict of interests to declare.

Background

A 62-year-old male had a dual chamber ICD (Abbott Gallant) implanted for probable Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC). He contacted the pacing department with symptoms of breathlessness when walking up a hill and mentioned that he thought he might have received a shock.

The device detection parameters were as follows:

- VT-1 Monitor Zone 130bpm

- VT-2: 187bpm, 30 intervals with ATP & shocks

- VF: 230bpm, 16 intervals with ATP whilst charging and shocks

- SVT discrimination dual chamber on.

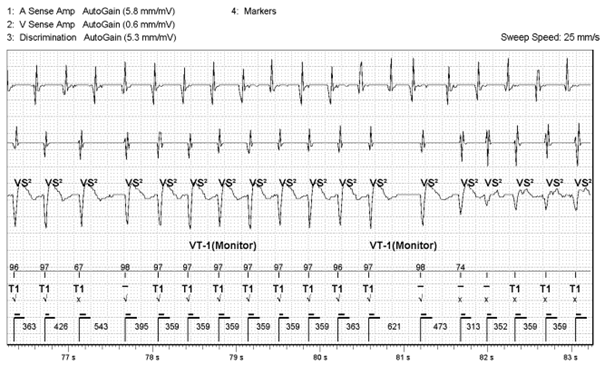

Below is the EGM that was sent via remote monitoring.

Figure 1: Stored EGM

QUESTION 1

What is the arrhythmia?

Definitely atrial tachycardia with rapid ventricular response

Probably atrial tachycardia with rapid ventricular response

Cannot say with any degree of certainty

Probably ventricular tachycardia

Definitely ventricular tachycardia

Answer

Probably Atrial tachycardia with rapid ventricular response – see below

QUESTION 2

What information would you want to ensure diagnostic certainty?

Device histograms

Historic ECGs

V EGM in sinus rhythm

Therapy summary showing patient activity levels

Patient history around the event

Current 12 lead ECG

All are relevant

Other information

Answer

All are relevant

Explanation

Irrespective of device algorithms, here, more A’s than V make AT more likely, but the differential diagnosis lies with a dual tachycardia (AT and VT) or with AVNRT with lower common pathway block.

So what supporting evidence is there for AT vs DT?

- In these traces we also don’t see the onset of the actual tachycardia (i.e. the atrial component) leading us to assume that the atrial rhythm may be a persistent atrial tachycardia and the device has ‘triggered’ only because the V has entered tachycardia zones. Knowing if the patient is in a longstanding AT is information that would help us understand the arrhythmia. The device AT counters and atrial and ventricular histograms might shed light on this. No previous history of AT would make it much more likely that this event was AT with rapid ventricular conduction. Viewing historic ECGs in the case records and confirming historic sinus rhythm adds weight to this new arrhythmia being atrial driven. The converse, however, of finding historic persistent AT does not tell us if this is AT with rapid conduction or AT with VT.

- In the initial part of this trace the morphology discriminator suggests a good match with the intrinsic ‘templated’ EGM. This is marked in Abbott devices as a tick below and a percentage score above the marker channel line. This would support a diagnosis of atrial tachycardia conducting rapidly. Note however that although high 90’s percentage matches are seen, some others with visually identical EGMs have low non-matching scores in the 60’s and as such the validity of this discriminator might be questioned. Personally reviewing the V EGM in sinus rhythm or AT with slower conduction might add certainty here. Additionally, viewing the current 12 lead ECG might help understand if a templating/morphology issue is likely. Patients with ARVC will commonly have a VT with a ‘left bundle branch’ morphology. If the current 12 lead ECG demonstrates that the patient intrinsically has a left bundle branch block, then there is a higher likelihood that the VT morphology will match the templated morphology, leading to a ‘false match’.

- Knowledge of the patient’s activity level from the device event summary or patient history can often help decide. It would be less common for the AV node to conduct rapidly at rest compared to when ‘active’.

- Given the intermittent ‘dropped’ V one might assume that this is Wenkebach in AT. However the norm would be for the RR interval to progressively shorten in Wenkebach, which it doesn’t clearly here. There is a pattern of 9 Vs and 1, occasionally 2, apparent dropped beats. The 2 ‘apparent’ dropped beats after a long cycle Wenkebach would be out of keeping for Wenkebach.

- A dot/interval plot is always useful here as it can show subtle variation in cycle length between the A and V channels not obvious on EGMs. Abbott ICDs don’t use/display a dot plot unlike Medtronic and Boston Devices however.

- Similarly some devices have a flashback report to allow EGM visualisation prior to the last event and can see increasing AV nodal conduction in AT or in this case maybe the onset of AT.

QUESTION 3

Has the shock been delivered appropriately?

No, the shock was inappropriate but the device functioned correctly

No, the shock was inappropriate and the device did not function correctly

Yes, the shock was appropriate and the device functioned correctly

Yes, the shock was appropriate but the device did not function correctly

Answer

No, the shock was inappropriate but the device functioned correctly

The device classifies this as SVT using Abbott’s rate branch discrimination (V<A) whereby the current ventricular rate is compared to the atrial rate. The EGM complex will then be checked against the SVT discrimination criteria and categorised according to the criteria set by the diagnosis parameter.

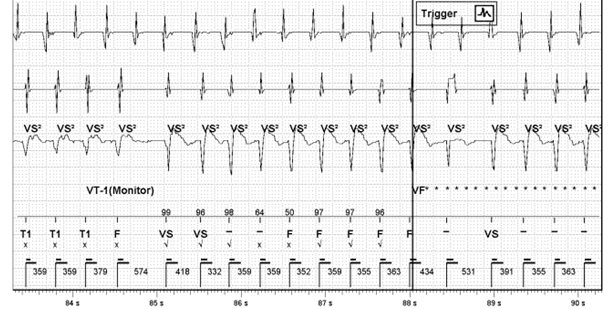

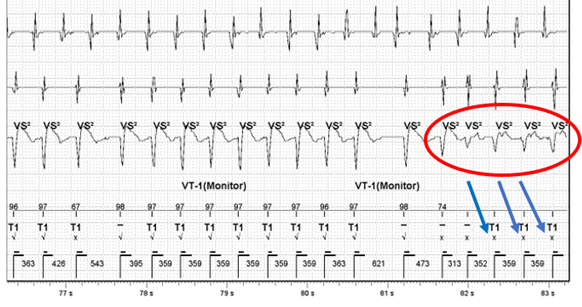

The arrhythmia starts off in the VT 1 zone, in this case set to a VT monitor zone, with T1 markers. There is then a sudden change in signal amplitude (circled in red) and EGM morphology mismatching (blue arrows). The reason for this could be related to:

- aberrancy in pre-existing rapidly conducted atrial tachycardia

- the development of VT in a pre-existing rapidly conducted atrial tachycardia or

- a change in morphology of a preexisting VT.

QUESTION 4

What arrhythmia is present in this change in morphology (and what is the supporting evidence for and against these possibilities and what further information would help?)

Definitely AT with rapid conduction still

Probably AT with rapid conduction still

Unsure, can’t be certain

Probably VT

Definitely VT

Answer

Unsure, can’t be certain

- The fact that the cycle length remains essentially the same would strongly support this being aberrant conduction of AT assuming the initial arrhythmia was AT with rapid ventricular response. A less common ‘fooler’ for this is a different exit in an inner loop VT. N.B. Inner loop VTs are reentrant cirucuits ‘protected’ within a scar that can have multiple exits from the scar giving different VT morphologies as the exits change but often without noticable change to cycle length as the inner loop circuit remains constant.

- The first beat of the clearly changed morphology is also unusual as it comes in at a cycle length shorter than the normal proposed AV conduction would allow (313 vs 359ms) and this wouldn’t generally happen with bundle branch block. This adds less support to the aberrant hypothesis.

- The beat before this short coupled beat appears now to be fusion between the 2 morphologies. This could represent VT fusing with conducted AT. Or perhaps there could be a single PVC fusing with conducted AT that conceals in the right or left bundle branch setting up aberrant conduction. It is unclear from the tracing.

- At the end, the shock ‘corrects’ both A and V channels so that doesnt help distinguish. Ongoing AT with a cardioverted V channel would have supported VT, as would ongoing VT with a cardioverted A channel.

As such, the cause of this temporary morphology and amplitude change remains uncertain.

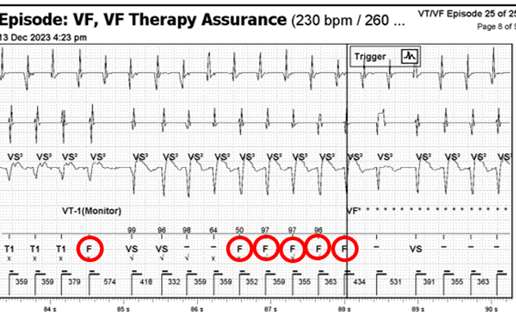

Figure 2: Signal change with morphology mismatching

QUESTION 5

What algorithm is triggered leading to a shock?

Answer

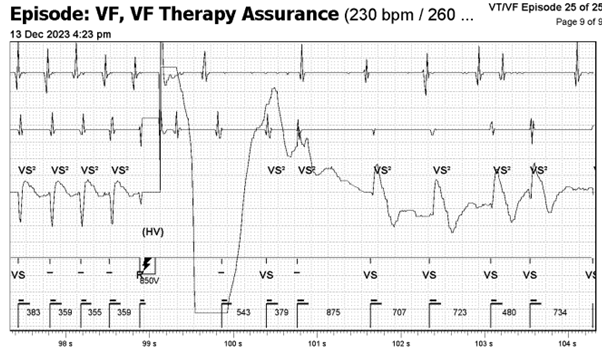

VFTA – Ventricular Fibrillation Therapy Assurance

Ventricular Fibrillation Therapy Assurance (VFTA) works in the background when the first fast interval average is detected, and will check the VFTA counter at 5 different points during the episode in the far-field sensing channel. VFTA was triggered due to the low amplitude counter which resulted in the VF zone being lowered to the lowest active treatment zone +100ms – i.e. 400ms. Six ‘VF’ markers are required to trigger VF therapy due to the VFTA algorithm dropping the number of intervals for detection (NID) from the programmed sixteen. Dropping the NID from sixteen to six accelerates time to therapy but the downfall of this is clear in the current EGM, whether this represents abberancy or non-sustained VT in rapidly conducted AT. VTFA only uses two independent counters; a low amplitude counter and a pause counter. The change in amplitude and morphology activated the low amplitude counter as at least two of the beats (circled in red) had signals measuring between 0.3 – 0.6mV. This triggered VFTA which caused the device to start charging due to satisfying the NID criteria of six (Figure 3, circled in red). This leads to an inappropriate shock for the patient but is algorithmically correct device function.

Figure 3: F markers causing device to start charging

VFTA is an algorithm that identifies polymorphic VT/VF that is at risk of being under-sensed. It does this by assessing sensing on the discrimination channel when a ventricular event is ongoing.

The algorithm works by using two independent counters, and is triggered when either one is true. A low amplitude counter looks for consistently small signals (0.3 – 0.6mV) and increments the counter by one. This triggers if the counter is >2. Large signals (>0.6mV) resets the counter to zero. The pause counter looks for signal dropout, which is defined as no sensing present. Two seconds without a VS2, increments the counter by one and large signals (>1mV) with a VS2 resets the counter to zero. This triggers if the pause counter in >1. Once VFTA is triggered a number of parameters are changed:

1) Detection is switched to single therapy zone – VF only

2) New VF detection rate is decreased to the lowest programmed active therapy zone + 100ms (400ms max)

3) Number of intervals to detection is decreased to 6

4) End of episode (previously Return to Sinus) is increased to 7 intervals

5) Permanently programmed VF zone therapies are used

VFTA has been evaluated retrospectively on >500,000 EGMs from 20,000 devices with the results highlighting that the algorithm altered high voltage therapy in 0.34% (67/20,000) of devices with an 81.9% episode positive predictive value and 79.1% true positive rate. VFTA delivered high voltage therapy to 0.22% (44/20,000) of the devices that experienced at least one potentially undertreated VT episode (Wilkoff et al, 2022). Overall, the results of Wilkoff’s study were positive in that the VFTA algorithm delivered high voltage therapy to 86% of patients who would have otherwise been untreated for potentially life-threatening arrhythmias. However, it must be appreciated that the validation used derived data as opposed to real-world prospective data and therefore might lack the rigour associated with prospective clinical trials.

A noticeable finding that warrants recognition includes the fact that a small number of patients would have received inappropriate therapy (0.07%, 14/20,000) if VFTA was programmed on due to noise oversensing (4), physiological oversensing (4), and SVT (6)However, this can be mitigated with appropriate discriminator programming in most cases as suggested by Stroobandt and colleagues (2019).

Although the current patient received an inappropriate shock, the benefits far outweigh the risk as evidenced by Wilkoff’s validation study as well as a handful of case reports that demonstrate the effectiveness of the algorithm (Bera et al, 2022; Brignoli et al, 2023). It is crucial for the Physiologist/Healthcare Scientist to recognise inappropriate device therapy and to make a clinical decision on next steps for device programming as well as seeking advice if needed.

References:

- Bera, D., Mani, S., Sen, R., Majumder, S., Halder, A. and Ray, A. (2022) Inappropriate ventricular fibrillation annotation and defibrillator discharge despite the same tachycardia cycle length in ventricular tachycardia-1 zone in an Abbott defibrillator – What is the mechanism? Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 46 (2), pp. 169-171.

- Brignoli, M., Mattera, A., Chianese, R., Simonette, A., Vittoria, D. and Viscusi, M. (2023) Real-world use of a novel ventricular tachycarrhythmia detection algorithm: A case report. Heart Rhythm. 9 (12), pp. 929-934.

- Stroobandt, R.X., Duytschaever, M.F., Strisciuglio, T., Heuverswyn, F.E.V., Timmers, L., De Pooter, J., Knecht, S., Vandekerckhove, Y.R., Kucher, A. and Tavernier, R.H. (2019) Failire to detect life-threatening arrhythmias in ICDs using single-chamber detection criteria. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 42 (6), pp. 583-594.

- Wilkoff, B.L., Sterns, L.D., Katcher, M.S., Upadhyay, G., Seizer, P., Kang, C., Rhude, J., Davis, K.J. and Fischer, A. (2022) Novel ventricular tachyarrhythmia detection enhancement detects undertreated life-threatening arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 02. 3 (1), pp. 70-78.

NOTE: Edited by Simon Modi. All cases are reviewed for accuracy, but if you have concerns, please direct them via the contact form on the website.

Disclaimer: The British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS) collates submissions for the ECG/EGM challenge on this website. These submissions, along with any accompanying answers, are provided by external contributors and are published for informational purposes only. BHRS does not endorse, guarantee, or warrant the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of any submissions or answers provided.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.